what were the effects of the constitution? move the correct answers to the image of the preamble.

2.3 Constitutional Principles and Provisions

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is the separation of powers?

- What are checks and balances?

- What is bicameralism?

- What are the Manufactures of the Constitution?

- What is the Bill of Rights?

The Principles Underlying the Constitution

While the Constitution established a national authorities that did non rely on the back up of the states, information technology express the federal government's powers by listing ("enumerating") them. This practice of federalism (every bit we explicate in detail in Chapter 3 "Federalism") means that some policy areas are exclusive to the federal government, some are exclusive to united states, and others are shared betwixt the 2 levels.

Federalism aside, iii key principles are the crux of the Constitution: separation of powers, checks and balances, and bicameralism.

Separation of Powers

Separation of powers is the allocation of three domains of governmental action—law making, law execution, and law adjudication—into three distinct branches of government: the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. Each branch is assigned specific powers that only it can wield (see Table two.1 "The Separation of Powers and Bicameralism as Originally Established in the Constitution").

Table two.1 The Separation of Powers and Bicameralism as Originally Established in the Constitution

| Branch of Government | Term | How Selected | Distinct Powers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative | |||

| House of Representatives | 2 years | Pop vote | Initiate revenue legislation; bring articles of impeachment |

| Senate | vi years; 3 classes staggered | Election by state legislatures | Confirm executive appointments; confirm treaties; endeavor impeachments |

| Executive | |||

| President | 4 years | Electoral Higher | Commander-in-chief; nominate executive officers and Supreme Court justices; veto; convene both houses of Congress; issue reprieves and pardons |

| Judicial | |||

| Supreme Court | Life (during skillful behavior) | Presidential appointment and Senate confirmation (stated more or less straight in Federalist No. 78) | Judicial review (implicitly in Constitution but stated more or less directly in Federalist No. 78) |

Effigy 2.vi

In perhaps the nearly abiding indicator of the separation of powers, Pierre L'Enfant'south programme of Washington, DC, placed the President's House and the Capitol at opposite ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. The plan notes the importance of the two branches existence both geographically and politically distinct.

This separation is in the Constitution itself, which divides powers and responsibilities of each branch in three distinct articles: Article I for the legislature, Commodity 2 for the executive, and Commodity Iii for the judiciary.

Checks and Balances

At the same time, each branch lacks full control over all the powers allotted to it. Political scientist Richard Neustadt put information technology memorably: "The Ramble Convention of 1787 is supposed to accept created a government of 'separated powers.' It did nothing of the sort. Rather, it created a regime of separated institutions sharing powers" (Neustadt, 1960). No branch can act finer without the cooperation—or passive consent—of the other two.

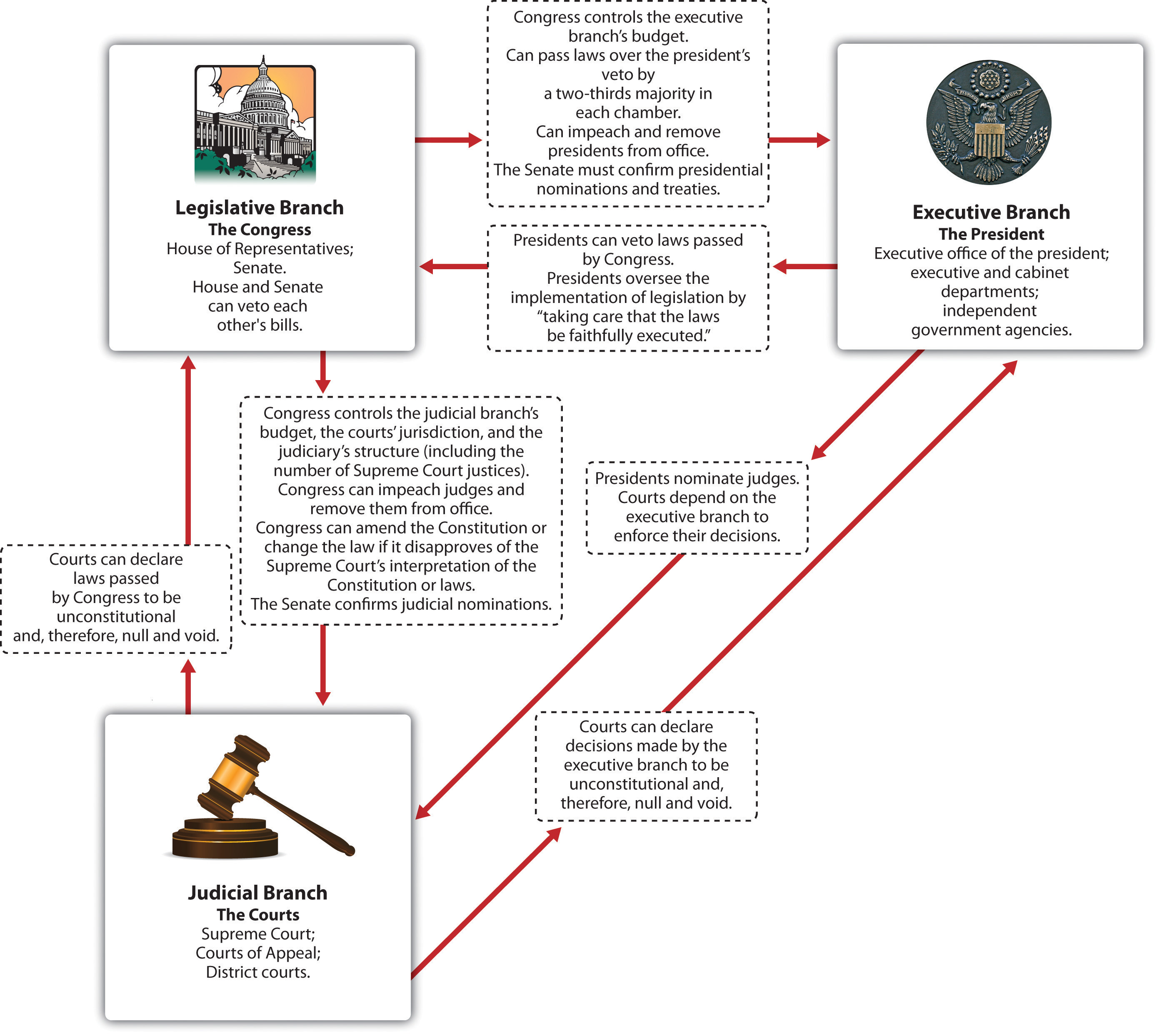

Well-nigh governmental powers are shared amid the various branches in a system of checks and balances, whereby each co-operative has ways to respond to, and if necessary, block the actions of the others. For case, merely Congress tin can pass a police force. But the president can veto it. Supreme Court justices can declare an human action of Congress unconstitutional through judicial review. Figure two.vii "Checks and Balances" shows the diverse checks and balances betwixt the three branches.

Figure 2.vii Checks and Balances

Adapted from George C. Edwards, Martin P. Wattenberg, and Robert L. Lineberry, Authorities in America: People, Politics, and Policy (White Plains, NY: Pearson Longman, 2011), 46.

The logic of checks and balances echoes Madison'due south skeptical view of homo nature. In Federalist No. x he contends that all individuals, even officials, follow their own selfish interests. Expanding on this signal in Federalist No. 51, he claimed that officeholders in the three branches would seek influence and defend the powers of their respective branches. Therefore, he wrote, the Constitution provides "to those who administer each department the necessary ramble means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others."

Bicameralism

Government is made nevertheless more circuitous by splitting the legislature into two separate and singled-out chambers—the House of Representatives and the Senate. Such bicameralism was common in land legislatures. 1 chamber was supposed to provide a shut link to the people, the other to add wisdom (Forest, 1969). The Constitution makes the 2 chambers of Congress roughly equal in power, embedding checks and balances inside the legislative branch itself.

Bicameralism recalls the founders' doubts virtually majority dominion. To check the House, directly elected by the people, they created a Senate. Senators, with six-year terms and election by state legislatures, were expected to work slowly with a longer-range understanding of problems and to manage popular passions. A story, possibly fanciful, depicts the logic: Thomas Jefferson, back from French republic, sits downwardly for coffee with Washington. Jefferson inquires why Congress will take ii chambers. Washington asks Jefferson, "Why did yous pour that java into your saucer?" Jefferson replies, "To absurd information technology," following the custom of the time. Washington concludes, "Even and so, nosotros pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to absurd information technology" (Fenno Jr. 1982).

The Bias of the Organisation

The U.s. political organization is designed to prevent quick understanding inside the legislature and between the branches. Senators, representatives, presidents, and Supreme Courtroom justices have varying terms of offices, distinctive ways of selection, and different constituencies. Prospects for disagreement and conflict are high. Accomplishing any goal requires navigating a complex obstacle course. At any point in the process, action tin be stopped. Maintaining the status quo is more than likely than enacting significant changes. Exceptions occur in response to dire situations such as a fiscal crisis or external attacks.

What the Constitution Says

The text of the Constitution consists of a preamble and vii sections known every bit "articles." The preamble is the opening rhetorical flourish. Its kickoff words—"We the People of the U.s.a."—rebuke the "We the States" mentality of the Articles of Confederation. The preamble lists reasons for establishing a national government.

The first three articles ready upwards the branches of government. We briefly summarize them here, leaving the details of the powers and responsibilities given to these branches to specific chapters.

Article I establishes a legislature that the founders believed would make up the eye of the new regime. By specifying many domains in which Congress is allowed to act, Article I also lays out the powers of the national government that we examine in Affiliate 3 "Federalism".

Article II takes up the cumbersome process of assembling an Balloter College and electing a president and a vice president—a process that was later modified past the Twelfth Amendment. The presidential duties listed here focus on war and management of the executive co-operative. The president's powers are far fewer than those enumerated for Congress.

The Constitutional Convention punted decisions on the structure of the judiciary below the Supreme Court to the starting time Congress to decide. Article 3 states that judges of all federal courts hold role for life "during good Behaviour." Information technology authorizes the Supreme Courtroom to make up one's mind all cases arising under federal law and in disputes involving states. Judicial review, the primal power of the Supreme Courtroom, is non mentioned. Asserted in the 1804 case of Marbury 5. Madison (discussed in Chapter xv "The Courts", Section 15.2 "Power of the United states of america Supreme Courtroom"), it is the power of the Court to invalidate a police passed by Congress or a decision made past the executive on the ground that information technology violates the Constitution.

Article IV lists rights and obligations among the states and between the states and the national government (discussed in Affiliate iii "Federalism").

Article V specifies how to amend the Constitution. This shows that the framers intended to have a Constitution that could be adapted to changing conditions. There are two ways to propose amendments. States may telephone call for a convention. (This has never been used due to fears it would reopen the entire Constitution for revision.) The other fashion to propose amendments is for Congress to laissez passer them by a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate.

Then there are two ways to approve an amendment. One is through ratification past 3-fourths of country legislatures. Alternatively, an amendment can be ratified by three-fourths of specially convoked state conventions. This process has been used once. "Wets," favoring the cease of Prohibition, feared that the Twenty-Showtime Subpoena—which would have repealed the Eighteenth Amendment prohibiting the auction and consumption of alcohol—would be blocked by conservative ("dry out") state legislatures. The wets asked for specially chosen state conventions and quickly ratified repeal—on December 5, 1933.

Thus a constitutional amendment can be stopped by one-third of either chamber of Congress or one-fourth of state legislatures—which explains why there have been but twenty-seven amendments in over ii centuries.

Article Half-dozen includes a crucial provision that endorses the move away from a loose confederation to a national government superior to the states. Lifted from the New Bailiwick of jersey Programme, the supremacy clause states that the Constitution and all federal laws are "the supreme Law of the State."

Commodity Seven outlines how to ratify the new Constitution.

Constitutional Evolution

The Constitution has remained essentially intact over fourth dimension. The basic structure of governmental ability is much the same in the twenty-kickoff century as in the late eighteenth century. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, the Constitution has been transformed in the centuries since 1787. Amendments have greatly expanded civil liberties and rights. Interpretations of its language by all three branches of government have taken the Constitution into realms not imagined by the founders. New practices have been grafted onto the Constitution's ancient procedures. Intermediary institutions not mentioned in the Constitution accept adult important governmental roles (Ackerman, 2005).

Amendments

Many crucial clauses of the Constitution today are in the amendments. The Bill of Rights, the first x amendments ratified past the states in 1791, defines ceremonious liberties to which individuals are entitled. Later on the slavery issue was resolved by a devastating ceremonious war, equality entered the Constitution with the Fourteenth Amendment, which specified that "No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." This amendment provides the ground for ceremonious rights, and further democratization of the electorate was guaranteed in subsequent ones. The right to vote became anchored in the Constitution with the addition of the Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Xx-Quaternary, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments, which stated that such a right, granted to all citizens aged xviii years or more than, could not be denied on the basis of race or sexual practice, nor could it be dependent on the payment of a poll tax (Keyssar, 2000).

Constitutional Interpretation

The Constitution is sometimes silent or vague, making it flexible and adjustable to new circumstances. Interpretations of constitutional provisions past the three branches of government take resulted in changes in political system and practice.[1]

For example, the Constitution is silent most the part, number, and jurisdictions of executive officers, such as cabinet secretaries; the judicial system below the Supreme Courtroom; and the number of House members or Supreme Court justices. The kickoff Congress had to make full in the blanks, ofttimes past altering the law (Currie, 1997).

The Supreme Courtroom is today at center stage in interpreting the Constitution. Before becoming chief justice in 1910, Charles Evans Hughes proclaimed, "We are nether a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the Court says it is."[2] Past examining the Constitution'southward clauses and applying them to specific cases, the justices expand or limit the accomplish of constitutional rights and requirements. However, the Supreme Court does not e'er take the terminal discussion, since state officials and members of the national government's legislative and executive branches have their own agreement of the Constitution that they apply on a daily basis, responding to, challenging, and sometimes modifying what the Court has held (Devins & Fisher, 2004).

New Practices

Specific sections of the Constitution take evolved profoundly through new practices. Article Two gives the presidency few formal powers and responsibilities. During the first hundred years of the commonwealth, presidents acted in express ways, except during war or massive social alter, and they rarely campaigned for a legislative agenda (Tulis, 1987). Commodity II's brevity would exist turned to the office's advantage past President Theodore Roosevelt at the dawn of the twentieth century. He argued that the president is "a steward of the people…bound actively and affirmatively to practise all he could for the people." So the president is obliged to do whatever is best for the nation as long as it is not specifically forbidden by the Constitution (Tulis, 2000).

Intermediary Institutions

The Constitution is silent most various intermediary institutions—political parties, interest groups, and the media—that link government with the people and bridge gaps acquired by a separation-of-powers system. The political process might stall in their absenteeism. For example, presidential elections and the internal organisation of Congress rely on the political party system. Involvement groups stand for different people and are actively involved in the policy procedure. The media are central for carrying information to the public most authorities policies as well every bit for letting government officials know what the public is thinking, a procedure that is essential in a democratic system.

Key Takeaways

The Constitution established a national government distinguished by federalism, separation of powers, checks and balances, and bicameralism. It divided ability and created conflicting institutions—between iii branches of government, beyond two chambers of the legislature, and between national and country levels. While the structure it created remains the same, the Constitution has been changed by amendments, interpretation, new practices, and intermediary institutions. Thus the Constitution operates in a system that is autonomous far beyond the founders' expectations.

Exercises

- Why was disharmonize between the different branches of regime congenital into the Constitution? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a system of checks and balances?

- How is the Constitution different from the Manufactures of Confederation? How did the authors of the Constitution address the concerns of those who worried that the new federal government would be too potent?

- What do you think is missing from the Constitution? Are there any ramble amendments you would advise?

References

Ackerman, B., The Failure of the Founding Fathers: Jefferson, Marshall and the Ascent of Presidential Democracy (Cambridge, MA.: Belknap Printing of Harvard, 2005).

Currie, D. P., The Constitution in Congress: The Federalist Period, 1789–1801 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

Devins, N. and Louis Fisher, The Democratic Constitution (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2004).

Fenno Jr., R. F., The United States Senate: A Bicameral Perspective (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1982), 5.

Keyssar, A., The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the U.s. (New York: Basic Books, 2000).

Neustadt, R. E., Presidential Power (New York: Wiley, 1960), 33. Of course, whether the founders intended this outcome is still open to dispute.

Tulis, J., The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987).

Tulis, J. Thousand., "The Two Constitutional Presidencies," in The Presidency and the Political System, 6th ed., ed. Michael Nelson (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2000), 93–124.

Wood, One thousand. Southward., The Creation of the American Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), chap. 6.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/americangovernment/chapter/2-3-constitutional-principles-and-provisions/

0 Response to "what were the effects of the constitution? move the correct answers to the image of the preamble."

إرسال تعليق